A Land Reform in Ancient China that Continues to Influence the Present(Warring State 13)

Volume 3 - The Reforms of Shang Yang III

Previous Chapter :The Core Logic of the Most Influential Political Reform in Ancient China(The Reforms of Shang Yang II)

Shang Yang’s reform can be distilled into two primary categories: Land Reform and Military Reform.

Let us first examine land reform.

The foremost measure in land reform was: All land was no longer subject to feudal enfeoffment.

Today, we speak of China transitioning from millennia of "Feudal Systems" to Socialist.

Historians often label the period from Spring and Autumn(770BC) times to the late Qing dynasty(1840AD) as "Feudal Systems," but this is actually quite inaccurate.

For after Comrade Gongsun Yang's sweeping reforms, the Feudal System gradually crumbled—replaced by the "Commandery-County System" (郡县制)that endured for over two thousand years.

No more enfeoffment or vassal kingdoms. The land became directly administered by the country. “You might be a local official, but you were no longer a local king.”

Shang Yang divided the entire territory of Qin State into 31 counties, each governed by a magistrate (县令) and a deputy (县丞).

In the past, feudal lords held absolute authority—but from this point onward, they were stripped of power.

At most, lords retained nominal ownership of their former fiefs' property, but personnel appointments? Forget it.

The people now only belonged to the state.

Local governance shifted to county magistrates—but these magistrates merely administered civilians on the state's payroll. Taxation and conscription no longer served the lords; all authority flowed directly to the central government.

Moreover, every newly conquered territory was immediately reorganized into commanderies and counties, with centrally appointed officials taking office.

The Result:

Former feudal lords were reduced to landlords.

Once-armed factions degenerated into glorified rent collectors.

"The subordinates of my subordinates do not listen to me!"

The commandery-county system perfectly fixed this loophole—from now on, all human resources belong solely to the central government.

After replacing Feudalism with the Commandery-County System, the rule became:

"Within my territory, you obey the central authority. Every individual is now my subordinate."

This change carried immense historical significance, profoundly influencing China's political landscape for over two thousand years—up to the present day.

Even now, China's systems of provinces, cities, counties, and villages still follow this very logic.

This system has endured two thousand years of turbulence, conclusively proving its maturity and stability.

For the central government, the so-called "Commander-County System" acts like a ruling straw that pierces straight to the bottom—ensuring seamless control.

On a deeper level, Shang Yang's reforms paved the way for China's centralized authority throughout history.

The Second Task of Land Reform: Changing the Land System and Taxation Method

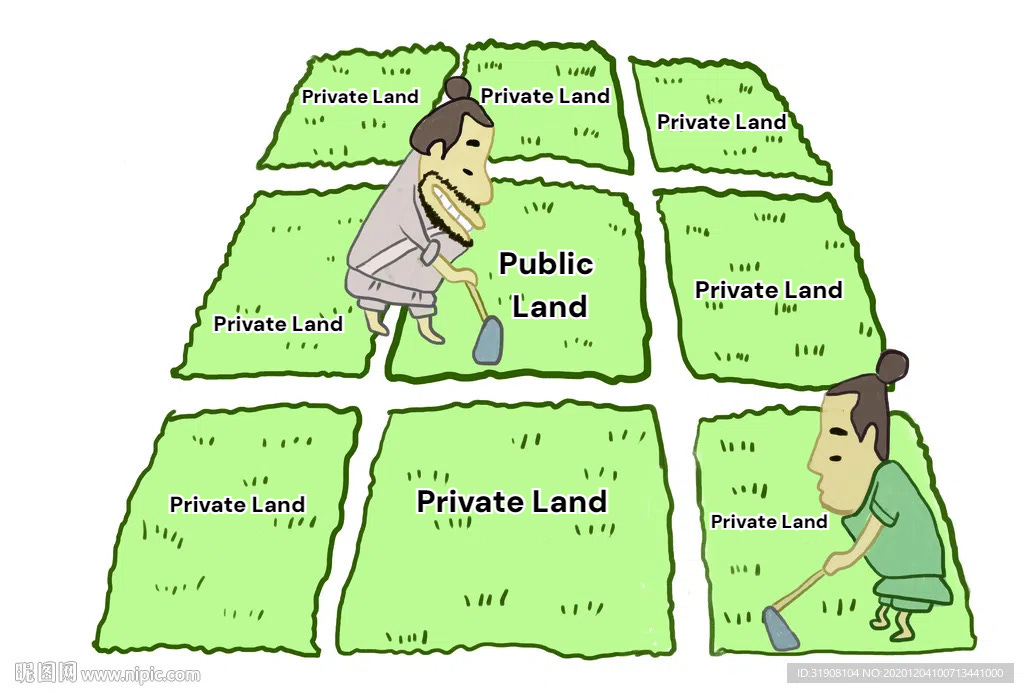

In the past, the common method was the "well-field system" (井田制). As we discussed in the Chapter Zero, it divided a plot of land into a nine-square grid—the central square was public land, while the remaining eight were private fields. Laborers had to work the public land first before tending to their own.

This arrangement was extremely inconvenient for leadership.

Shang Yang abolished this system in Qin. He removed boundary paths (阡陌), established a road network, and divided rural areas into uniformly sized plots of land. This made land calculation visually verifiable. The land was then registered and allocated to peasants.

Next came tax reform:

"I grant you land. Each year, I estimate its expected yield—you must pay a fixed amount of grain and fodder, regardless of how much you actually harvest. Succeed or fail, it’s your responsibility."

Miss the tax deadline? Qin’s laws lovingly prescribe foot amputation.

Thus, every serf was forced to work like their life depended on it.

After land registration, allocation to peasants, and binding the common people to the land, Shang Yang implemented a groundbreaking high-tech reform:

The Household Registration System (户籍制度)

This system was absolutely revolutionary. Not only is it still in use today, but it also completely clarified the nation’s demographic and economic foundation.

The Household Registry not only conducted a full census of Qin’s population, but Shang Yang also imposed further restrictions:

Mandatory household division upon reaching adulthood (no more multi-generational cohabitation).

Restricted free travel—leaving the village required travel permits.

Private inns were banned (no unauthorized lodging).

The skies of Qin forever bore five words: "No one escapes control!"

Shang Yang designed Qin’s administrative structure as a pyramid:

Commanderies (郡Jun) → Counties (县Xian) → Townships (乡Xiang) → Villages (亭Ting) → Groups of Hundred (里Li) → Groups of Ten (什Shi) → Groups of Five (伍Wu).

Chinese textbooks only cover down to the township level (乡). Today, we’ll delve deeper into the grassroots structure—the higher levels (like commanderies and counties) will be systematically explained later when Liu Bang enters Xianyang.

Five households formed one "Wu" (伍), led by a Wu Chief (伍长).

Ten households formed one "Shi" (什), led by a Shi Chief (什长).

One hundred households formed one "Li" (里), led by a Li Chief (里长).

Ten "Li" formed one "Village" (亭), led by a Village Chief (亭长).

Ten "Village" formed one "Township" (乡), led by a Township Chief (乡长).

Ten "Townships" formed one "County" (县), led by a Magistrate (县令) or County Head (县长).

(Counties with over 10,000 households had a "Magistrate"; those with fewer had a "County Head.")

Ten "Counties" formed one "Commandery" (郡), led by a Commandery Governor (郡守).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to History of China to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.