How Was China's First Elite Cavalry Force Created?(Warring States 30)

The Reform and Rise of the State Zhao 4

Previous Chapter :The Challenge of Raising an Elite Cavalry in the Ancient World(Warring States 29)

After deciding on reform, Zhao Yong赵雍 didn’t charge ahead recklessly like Shang Yang商鞅. Instead, he proceeded gradually, starting with pilot programs.

The first step was to launch a pilot in the north.

He formalized the border garrison troops, who had already adapted on their own, into official cavalry units. They were given designations, benefits, and full organizational structure, with the state overseeing selection and training.

The message was: “You are no longer just border guards; you are the kingdom’s special forces! Better rations and allowances are here—now excel at your jobs!”

The second step was to conduct military exercises in the north.

When facing this “pilot unit” that had adopted nomadic tactics, the northern nomadic peoples lost their advantage in mobility. Meanwhile, their weaknesses—poor discipline, inferior equipment, and lack of structured tactics—were greatly exposed. The pilot unit achieved a series of victories in military engagements against the northern nomadic tribes.

Here, we need to briefly explain the tactics of nomadic cavalry during the Warring States period.

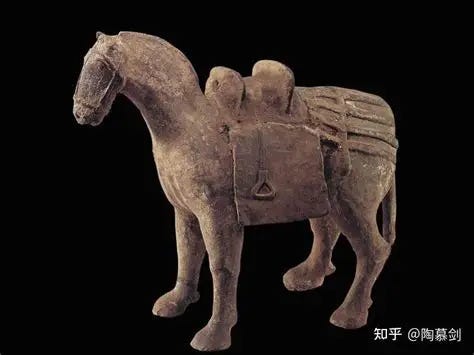

When we think of cavalry, we usually imagine their overwhelming advantage against infantry. However, the true, massive military dominance of cavalry wasn’t fully realized until the Northern and Southern Dynasties period(420-589AD), when stirrups became standard equipment and cavalrymen were armed with long lances. That’s when the infantry’s nightmare truly began.

Because back then, no matter how thick your armor was, a lance wielded from a galloping warhorse could finish you off.

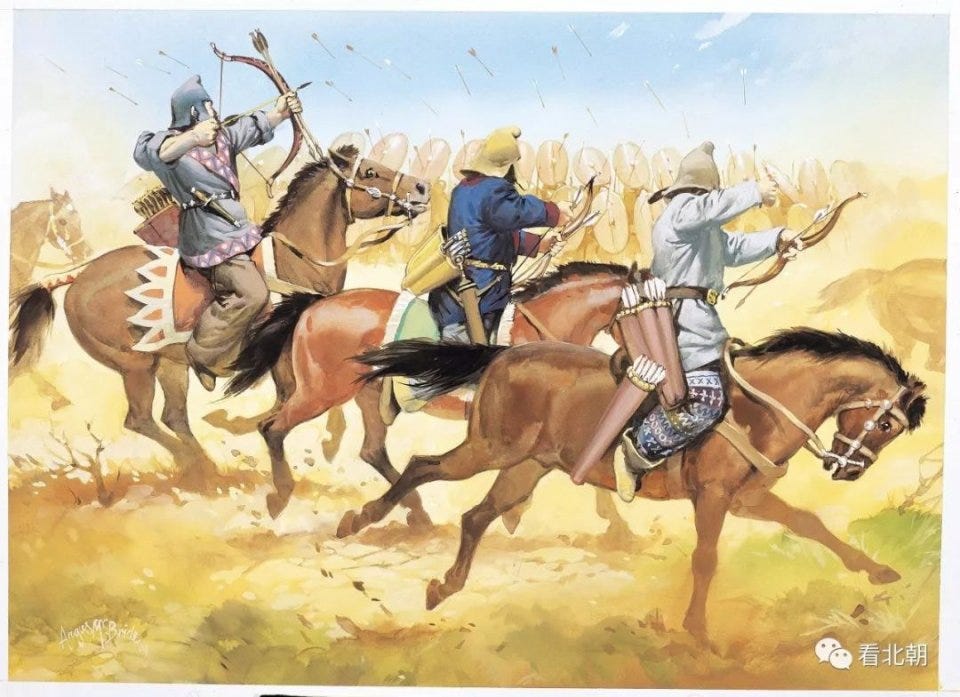

But the Warring States period was different. The primary tactic here was horse archery, and the reason, again, relates to the stirrup.

Let’s talk about the importance of the stirrup. Since stirrups didn’t exist back then, riders couldn’t brace themselves properly on horseback.

This meant you could only shoot arrows from a distance or get close and slash with a sword.

Long weapons were impractical because your legs couldn’t provide leverage. So, the traditional image of Guan Yu关羽 brandishing a 90-pound Green Dragon Blade isn’t accurate—he would have fallen off his horse after just a few swings.

Before the Han Dynasty(202BC-220AD), the Chinese peoples also adopted the nomadic style of mounted archery in cavalry combat.

Engagements typically started with exchanges of arrows from a distance. If opponents closed in, sabers were used. The horse’s speed couldn’t be fully leveraged for forceful strikes; its primary advantage was mobility—allowing hit-and-run tactics: after striking, you could escape pursuit, or ensure the enemy couldn’t flee if you had the upper hand.

The greatest threat from nomadic armies wasn’t necessarily annihilating your forces outright. It was their ability to raid, plunder, and then vanish—you couldn’t catch them, and you had no idea where to find them.

However, by the time of Wei Qing卫青 and Huo Qubing霍去病(before 100 BC), the Chinese side had already pioneered tactical innovations. Long lances became standard equipment, and military tactics evolved into early-stage defense with heavy armor, followed by chasing down the enemy and thrusting with long lances.

But a problem arose: without stirrups to brace against, and given that force is mutual, the powerful recoil from thrusting could easily unhorse the attacker.

This often led to fall injuries or being trampled, resulting in a scenario where you inflict a thousand casualties on the enemy at the cost of eight hundred of your own.

However, in this kind of warfare, the agricultural civilizations held a significant advantage. Even if one of our wounded soldiers was later discharged, he could still return to farming. But the nomadic peoples didn’t have a large pool of manpower; if a man fell from his horse, he was essentially lost.

Not only was this attritional tactic favorable, but charging forward with a lance required little specialized training—basic horsemanship was sufficient.

This dramatically reduced the massive cost associated with training in mounted archery.

Consequently, it ultimately became a war of attrition for Emperor Wu of Han汉武帝(R. 141-87BC) against the Xiongnu匈奴(ancestor of Huns).

“We are the Chinese; don’t try to outbreed us.”

However, even with reduced training costs, maintaining a large-scale cavalry force remained a massive burden for any state. Even the mighty Emperor Wu of Han, who squeezed the resources of the Chinese heartland to the breaking point, could only muster a total of 100,000 elite cavalry for the two-pronged offensive at the peak of the Campaign to the north of the great desert.

The reason nomadic societies relied primarily on mounted archery was tied to their entire way of life. Their daily life involved hunting on horseback, and warfare was simply an extension—hunting people instead of animals. Furthermore, the steppes lacked key military resources like abundant iron and quality wood, as well as the crucial technologies to work them, making it impossible for them to produce long weapons in quantity.

Being largely limited to long-range archery meant the nomadic people’s military advantage during the Warring States period wasn’t as overwhelming as one might think.

The quality of many of their key weapons was subpar. Many of their arrowheads were still made of animal bone, with questionable sharpness. So, while they might be effective for hunting game, against Zhao赵 cavalry equipped with proper defensive gear, a single shot was unlikely to be fatal.

In contrast, Zhao’s manufacturing and craftsmanship were reliable and advanced for the time.

Facing a Zhao military that could produce effective armor, while the nomads themselves, still clad mostly in animal hides, lacked good protective gear, what advantage did the nomadic tribes really have against this professionally armed, mobile Zhao archery corps?